--by

Josh Suchon

Note to readers: The feedback on

the “You Were Lucky, Hershiser” story was so positive, and triggered so many

memories from a childhood where my playground was the Oakland Coliseum, I’ve

decided to share more of these stories. I’m blatantly stealing this idea from

“Cardboard Gods” author Josh Wilker, who used his baseball card collection to

tell the story of his childhood in the 1970s. Wilker gave me his blessing, so

I’m going to use my autograph collection to tell the story of my childhood in

the 1980s.

When I

reflect on my childhood experiences with Dave Henderson, the following items

come to mind first:

1, Hendu

often wore all-white jump suits and was totally paranoid that our Sharpies

would get on his clothing when he stopped to sign autographs in the player

parking lot.

2, Hendu

had not one, but two fan clubs in the Coliseum bleachers. “Hendu-land” was the

last section of bleachers in left-center before the batter’s eye. “Hendu’s Bad

Boy Club” was in right-center, a section without stairs going down because the

batting cage was below.

3, Hendu

had a gap between his front teeth, on display whenever he flashed that

awesomely goofy grin. He flashed that grin when he signed my “One Strike from

Boston victory” 1987 Fleer card, and somebody asked him about those playoffs.

4, Hendu’s

performance in 1988 made me forget about the departure of Dwayne Murphy, one of

my favorites and the last remaining member of the A’s 1981 playoff team.

4, Hendu’s

performance in 1988 made me forget about the departure of Dwayne Murphy, one of

my favorites and the last remaining member of the A’s 1981 playoff team.

5, Hendu

coined the term “Fly Boys” for the two biggest legends in the bleachers.

Mike

Kelly and Jay Didier were rock stars among the regulars who showed up for

autographs, chased batting practice home runs, cheered on the A’s from the

bleachers, stuck around postgame for more autographs, then did it all over

again the next day.

Their

rock-star status, at least to me, was based on their ability to fly down the

stairs. Yes, fly.

They put the open side of their gloves on the railing, bent their elbow so it was pointed down, leaned in, reached back with their bare right hand further up on the railing, and slid down -- knees bent, feet in the air, hair flying.

Their

feet never touched the steps. They were a blur. They were down the steps so

much faster than everybody else, they’d get just about any ball that didn’t

land in the seats.

In my last posting about Curt Young and Rick Honeycutt, I wrote about how Didier was

an older guru. You listened to Didier.

You

idolized Kelly. He invented the sliding

down the railing technique, and was clearly the best. He was a few years older

than me, and was an incredible athlete. I once played catch with him in the

parking lot – between autograph time, and BP time, you had to get your arm loose – and couldn’t believe his arm.

Mike

Kelly was like Kelly Leak from the Bad News Bears. Kelly even had long hair,

like the fictional Kelly.

I

wanted to be like Mike.

I

wanted to glide down those railings, using just my glove, my feet never

touching the steps, hit the ground, find the ball in the air, run underneath

it, and catch home runs on the fly. I wanted kids a few years younger than me

to idolize me and ask me to show them how I flew down the railing like that.

I went

to my high school on weekends – you know, so nobody would see me looking like

an idiot -- and practiced trying to slide down railings with my glove.

Try as

I might, I couldn’t do it. Couldn’t generate the balance. Couldn’t generate the

speed. Couldn’t generate the courage to go that fast, and trust myself that I

wouldn’t do a face-plant. I even tried to lather up my glove with oil for

better sliding. It didn’t work.

Best I

could do is run down about two-thirds of the way, and somewhat slide down the

last 4-5 steps. In reality, it was more like me jumping down the last steps

than gliding down on a glove.

Kelly

and Didier were among a group of about 20 that sat in the same bleacher section

each game: second section over from the steps in left field. When the A’s

reached the playoffs in 1988, the group didn’t have access to playoff tickets

because they weren’t official season-ticket holders, even though they went to

every game. The bleachers were sold day-of-game only.

That

group wrote a letter to then-A’s owner Walter Haas, explaining their situation

and asking for assistance. Not only did Haas make sure they were in the

Coliseum for every playoff game, he made sure they were seated in their section

and in the first two rows – their usual spot. (Another reason Haas was such a

beautiful man and owner.)

This

meant Kelly was in the front row, aisle seat, closest to the railing. Didier

was next to him.

In Game

Three of the 1988 American League Championship Series against the Red Sox,

Kelly accomplished something that I have no way to prove is true, but I can’t

imagine anybody else has ever equaled: catch three home runs in a single

playoff game.

Mark

McGwire, Carney Lansford and Hendu hit home runs over the left field wall in

about the same area. Kelly, flying down the railing, way before everybody else,

ended up with all three. (Ron Hassey, a lefty, pulled his home run to right

field.)

I

didn’t have tickets for that game. I remember watching it on TV with my dad,

seeing the blur that is Kelly flying down the stairs, and thinking, “I bet Mike

ended up with all those home runs.”

When I

got to the Coliseum the next day for Game Four, my guess was accurate. He got

’em all. Each ball was secured in a separate plastic bag with all the details, and he was

trying to get them autographed, just like he did with all his home run balls.

The dude was incredible.

Watching

Kelly was awesome, yet utterly intimidating. You had so few chances to get home

runs -- in batting practice or the game -- because he got so many. And if Kelly

didn’t get it, Didier would. You had to pick another section to patrol, but

their section was the prime real estate.

My

seats varied at the Coliseum. My dad bought 20 games annually from his friend

and the seats were incredible -- section 123, row 2, aisle seat 13 and 12 --

just one section over from the A’s dugout.

For the

other 20-35 games I would attend with my friends, we’d buy the cheapest seats

and bounce around. I loved the first row of the second deck, right behind home

plate, for the view of the field and the chance to get foul balls. Another

favorite spot was down the left-field line, near the A’s bullpen. We ended up

in the bleachers quite a bit too.

I still

ended up with about 25 major league balls over a four-year period. By comparison, 25 balls was probably a home stand for Kelly. If the baseball was a

brand-new white “pearl,” I’d use it to get autographs. The best part of getting a ball was actually bringing it to Little League practice, asking if somebody wanted to play catch, and waiting for them to notice what kind of ball we were using.

All the

baseballs that I obtained were during batting practice. Much to my dismay, I

never caught a home run ball.

On

opening day 1989, I thought for sure I had my first. My friends and I sat two

sections over from The Fly Boys, so we could be in the front row too, and have

a better chance.

Facing

Dave Stewart in his first major league at-bat, Ken Griffey, Jr. ripped a ball

into the left-center gap. Off the bat, I saw it coming right toward us. Without

hesitation, I sprinted down the steps, head down so I wouldn’t trip, jumped the

last few steps, hit the ground, and realized that I was ahead of everybody.

This historic ball would be mine for sure.

Then I

realized why I was alone down there. The ball didn’t go over the fence. It

one-hopped the wall. It was only a double. When I came back up the stairs, I

was mocked for thinking the ball was gone. I couldn’t help it. If I was going

to beat “The Fly Boys” for a ball, I had to run before I could judge if the

ball was gone or not.

Mike

Kelly and Jay Didier were everywhere. I went to spring training with my Dad,

and who did I see there? Mike and Jay.

It

seemed like Kelly always had the best 8x10 photos to get signed. You’d usually

see the same photos at card shows, but Kelly had photos that I never saw

anywhere else. I asked him one day where he gets them, and he told me about a

store along the Peninsula, close to where he lived.

By

then, my friend Todd Strong had his driver’s license, so we made our way to the

store. The selection was heaven. They had 8x10 photos of the stars, the top

prospects, and the most random players. They had 8x10 photos of practically

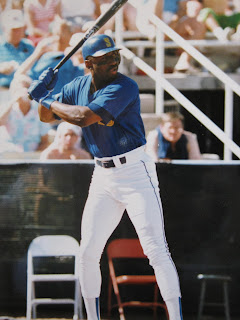

every A’s player, including Hendu, so I bought one and got it signed.

Going

through the photo binders one day, I did a double-take at the background of an

8x10 Jeffrey Leonard photo. A lot of those photos were taken in spring

training. I recognized the Mariners old field in Tempe, and recognized the guy

in the background with his shirt off and wrapped around his head.

It was

Mike Kelly.

He was

everywhere.

|

| That's Mike Kelly under Leonard's arms. |

***

Mark

Saxon was the A’s beat writer for The

Oakland Tribune from 2000-03. I was the Giants beat writer those four

years. Saxon took a job with The Orange

County Register after the 2003 season, and I was given the choice of

whether to continue covering the Giants or switch to the A’s.

The

Giants are the bigger story in the Bay Area by a longshot, but the A’s mean

more to The Oakland Tribune. It was a

guarantee I’d be above the fold on the front page of the sports section every

day. The A’s still had Tim Hudson, Mark Mulder and Barry Zito for star power,

and I could get away from the circus of covering Barry Bonds every day. The

decision was a no-brainer.

Besides,

after all those years getting Sharpie Scribbles at the Coliseum, telling World

Series heroes they were lucky, chasing Jose Canseco around the parking lot, and

having a man-crush (before I knew what a man-crush was) on some dude who slid

down the railing named Mike Kelly, it was time to come full-circle and cover

the A’s.

The

Coliseum, as my work place, was much different than the Coliseum as my

childhood playground.

The

renovations to accommodate the Raiders ruined the bleachers. They were never

the same. Most of the characters from those days stopped going to games, or sat

somewhere else. Still, every day when I was on the field during batting

practice, I’d look into the crowd and wonder if I’d ever see Mike Kelly or Jay

Didier again.

For

four years of my childhood, they were everywhere.

Now,

they were gone.

As I’ve

mentioned before, I didn’t talk about my childhood at the Coliseum very often

with work colleagues. I’m sure they didn’t care, I didn’t want them to think I

was some closet A’s homer who wasn’t objective, and it’s somewhat embarrassing

what a baseball nerd I was back then.

One

night though, I think at a bar in Kansas City over multiple vodka and red

bulls, I was out with one of the guys from the A’s television crew named David

Feldman. The conversation turned to the Coliseum bleachers in the late 1980s.

Turns out, he always sat in the same bleacher section with Mike Kelly and Jay

Didier.

Feldman

didn’t know where the “Fly Boys” are now, but he knew them well back in the

day.

We

didn’t know each other in the 1980s, mostly because Feldman wasn’t into getting

autographs, but we knew many of the same Coliseum Characters, and we’d spent

countless nights sitting very close to each other at the Coliseum as

teen-agers.

Now, we

were on the road with the A’s, talking about Mike Kelly.

What a

life.

***

|

| The last remains of my ball collection from the 1980s. |

When I

was going through my Sharpie Scribbles recently, I saw Mike Kelly’s name and

phone number written on the bottom of the cardboard box that I always brought

to games to store my cards.

For

over two weeks, I debated whether I should call the number. I knew it was a

land-line. Nobody had cell phones back then. I figured it was his parent’s

number. I could explain my story, explain this blog, and maybe they would give

me his number.

Last

night, I finally decided to go for it. I dialed the number. Not surprisingly,

nobody at that number knew Mike Kelly. I was actually relieved.

Sure,

it would be fun to talk with him, see if he remembered me, reminisce about

those good ol’ days, ask how he invented the sliding down the handrail

technique, and hear what he’s doing with his life these days.

Then

again, what if he was a mess? Or a drug addict? Or fat and unable to play

catch? Or worse yet, what if he still went to games and tried to get autographs

and home runs balls, and hadn’t cut his hair since the 80s?

I’d

rather remember Mike Kelly as the guy who ruled the Coliseum outfield beyond

the fences, the way Dave Henderson ruled the Coliseum outfield inside the

fences.

No comments:

Post a Comment